Fares please! Ticketing on London’s public transport since 1860

Introduction

Since the earliest days of public transport in London there have been tickets, and lots of them. They have been used for buses, trams and trains on countless millions of journeys to and from work, as well as to shops, theatres, football matches and the rest.

Yet in the twenty years since Transport for London (TfL) introduced the Oyster card in 2003, paper tickets have almost disappeared. The last bus tickets were issued in 2014, and today only a tiny proportion of Underground passengers are still using paper tickets and travelcards.

This story takes us on a visual tour of the changes in ticketing and fare collection since the nineteenth century.

On the roads, 1860s to 1960s

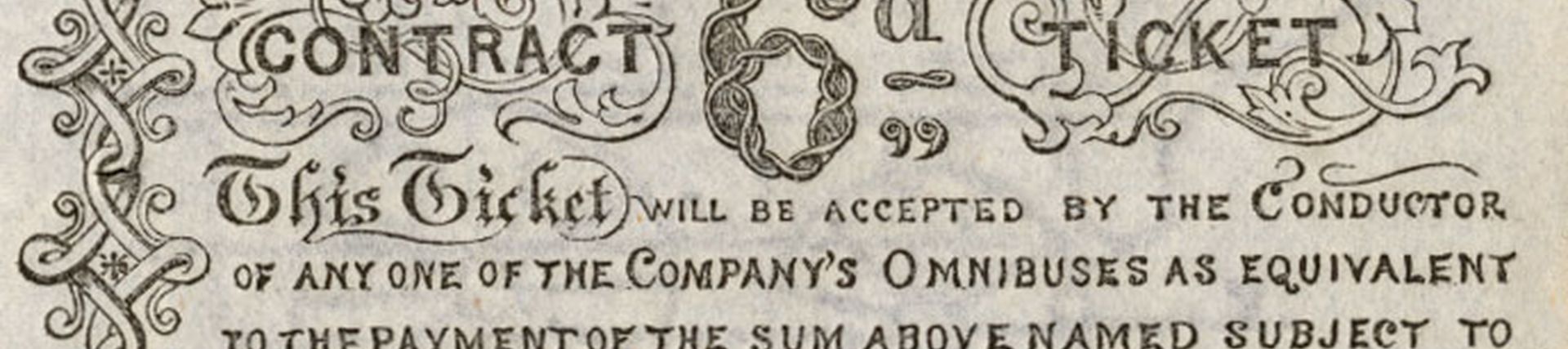

No tickets were issued on the first horse buses. But the largest company, the London General Omnibus Company (LGOC), did sell books of generic pre-paid tickets like this one in the 1860s.

Other early tickets, like this 1871 tram ticket, were torn from a roll by the conductor, and were barely the size of postage stamps.

The London Street Tramways company were soon issuing elaborate colour tickets, but they functioned mainly as advertisements for Epps Cocoa and had no route information.

Standardised pre-printed bus tickets for each route, with different colours for a range of distances and fare values, were introduced in the 1890s and were adopted by all London’s bus and tram operators. The system, developed by the Bell Punch Company, was complicated and costly but worked well, and continued with few changes for six decades.

Conductors selected the correct ticket for the fare from a wooden rack and clipped a small piece from each ticket with a Bell Punch machine to show where passengers got on. A bell rang for each ticket issued and the clipping was saved inside the machine. Conductors became known as ‘clippies’ as a result. If necessary, the clippings could be counted up and checked against the cash takings.

Other systems were trialled, but it was not until the 1950s that a reliable, flexible machine able to print tickets to order was introduced: the Gibson. The first prototype was designed by George Gibson, the manager of the London Transport (LT) ticket works in 1942. The route, ticket type, place boarded and fare could all be set by the conductor and printed from a roll with a quick succession of clicks, whirs and ker-chunks.

Underground tickets, 1860s to 1950s

The world’s first underground railway, the Metropolitan Railway, opened in London in 1863. By that time, the standardised ‘Edmondson’ pre-printed railway ticket system, named after a station master in the north of England in the 1840s, was well-established. Each new underground railway adopted the Edmondson system as the network grew, and in time the different companies started to co-operate and allow interchanges and joint ticketing.

In the 1920s, a range of machines operated by booking office staff started to appear. They printed and cut tickets from rolls for the most common destinations. The best of these was the AEG Rapid Printer, which was later made by Westinghouse in the UK, and remained in use until the 1980s. Self-service ticket machines also became more sophisticated in the 1920s and early 1930s, providing a range of tickets and giving change.

Automatic Fare Collection

By the late 1950s station ticket offices stocked a huge range of tickets, but most were only used rarely. Few travellers used passes, then known as season tickets. When the planning for the new Victoria line started, it was decided to try to automate the issuing and checking of the most popular tickets to save money and reduce queuing and fraud.

The first experimental ticket machines and automatic barriers were installed at a handful of stations in the mid-1960s, using tickets with magnetic code strips, devised by LT’s head of signalling, Robert Dell. The system became known as Automatic Fare Collection or AFC.

New horizons in the 1980s

The AFC system was installed on the Victoria line but did not deliver the promised levels of fraud reduction, and the gates were unreliable. Plans to extend it to the rest of the Underground were dropped, but London Transport continued research into a better system, which would evolve into the Underground Ticketing System (UTS) in the 1980s.

A new company won the contract to develop the system, pairing the established British outfit Westinghouse with Cubic, a US company with more experience in automated fare collection systems. Trials of a new ticket machine and automatic gates by Westinghouse Cubic in the early 1980s were a success, but progress to the full installation was slow due to upheavals at London Underground.

London Transport’s fare structures changed to a zone system at this time, simplifying ticketing and paving the way for a new generation of passes known as Travelcards, issued in daily, weekly, monthly and annual formats. Passengers paid for their journeys to and from work by bus or Tube in advance, and other trips over the same zones in the evenings or at weekends were free.

In 1985 the Capitalcard, which also served British Rail stations, was introduced. Some buses still retained conductors with the old faithful Gibson machines, but increasingly tickets were now bought from the driver through a range of different machines.

The first UTS ticket machines were installed on the Underground in 1987, with the automatic gates following in 1988. Most were in central area stations, with the work often combined with refurbishments.

Smartcards and Oyster

In 1990 London Underground held a trial of new Westinghouse Cubic smartcards to activate modified ticket gates at St James’s Park and Victoria stations, with technology from Cubic in the US. The trial used bulky ‘cards’ 5mm thick, but it was successful. The viability of the system was confirmed.

London Buses were also experimenting with smartcards in north London at this time, using a system called Buscom, originally developed for a ski lift in Ouluo, Finland. Cards were trialled first on a single route in 1992, then eventually on all routes serving Harrow bus station in a two-year trial starting in February 1994, including the first ‘pay as you go’ type cards.

To take the various trials further, LT engaged a consortium called Transys in 1998 to provide ticketing for their entire network and install touch-screen ticket machines and automatic gates throughout the Underground. Cubic Transportation Systems controlled one half of the consortium, but took over the whole project in 2010.

After years in development the first Oyster cards were issued to LT staff in 2002 and to the public in 2003. At first Oyster cards functioned as electronic Travelcards, with the ‘pay as you go’ function added in 2004. By 2008, 10 million cards had been issued. London Buses had been installing roadside ticket machines to reduce boarding times before Oyster, but these were used less and less as Oyster gained ground.

Contactless

Pay as you go with contactless payments by bank cards and smartphones launched on London’s buses in December 2012, and across Tube and London rail services in September 2014. Bus services became entirely cashless in July 2014.

In 2022 contactless journeys made up around 71% of all pay as you go journeys on Tube, bus and London rail services, more than double the figure for 2016.

TfL is now one of Europe’s largest contactless merchants, with around 1 in 10 contactless transactions in the whole of the UK taking place on the TfL network, and a third of the contactless journeys on the Tube are now being paid for with a smartphone or smartwatch. London Underground still issues around 25,000 paper tickets and passes a day, with that 1980s favourite the one-day Travelcard still holding its ground, but this number amounts to less than 1% of all journeys.