London’s electric trams and trolleybuses

Introduction

The arrival of the electric tram on London’s streets in the early 1900s brought cheap transport to the masses. In the 1930s, they were joined by electric-powered trolleybuses.

During their heyday, London had the largest tram and trolleybus system in the world.

The trolleybus superseded the tram, but both were eventually phased out in the 1950s and 1960s by a bus fleet that was cheaper to run.

New power

By the end of the 19th century, traffic was causing chaos on London’s streets. A new form of power was needed that would replace London’s enormous and costly horse population.

Electricity offered the best hope of a cleaner, cheaper and more efficient solution. The world’s first underground electric railway, the City & South London Railway (C&SLR), had opened in 1890. But while London’s underground network expanded over the succeeding decades, it was the tram that brought affordable electric-powered transport to millions more rapidly.

The arrival of the electric tram

The first commercially successful electric tramway was built by Werner von Siemens in Lichterfelde near Berlin, in 1881.

In Britain, development of electric tramways was slow. Funding was challenging and many local authorities opposed the disruption that the conversion to electricity would bring to their streets. Britain’s first electric tramway was opened in Blackpool in 1885, but London did not follow suit for another 16 years.

London United Tramways (LUT) began London’s first electric tram service on 10 July 1901, operating between Shepherd’s Bush, Hammersmith, Acton and Kew Bridge. The LUT’s Managing Director, Clifton Robinson, had worked on tramways in the USA and Bristol, and his company set about electrifying lines in west London using overhead wires.

Other lines quickly followed as local authorities and two other private companies began to operate services. By the end of 1901, the boroughs of East Ham and Croydon were running electric trams. By 1906, ten municipal systems had been set up.

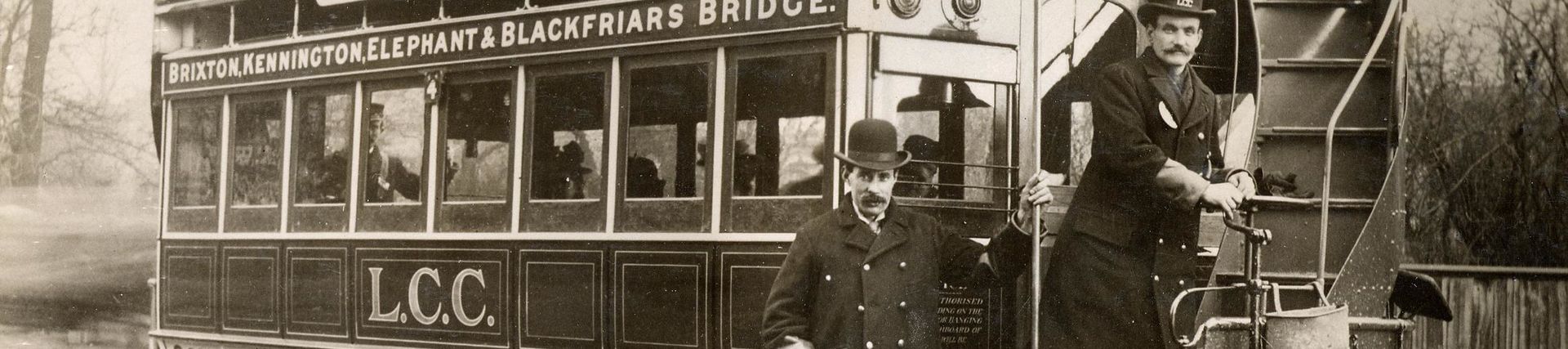

The London County Council

In central London, the London County Council (LCC) had started taking control of the horse tramways in 1896. Despite opposition from other operators, by 1899 it had taken over the principal lines in south London.

The LCC wished to electrify its lines but was faced with difficulties. It had adopted the ‘conduit’ system of supplying power by means of a live rail buried under the road surface, rather than the unsightly, if cheaper, overhead wires. The conduit track was expensive to build and maintain. The LCC opened its first line to Tooting in 1903, and by 1910 had electrified 120 route miles, making it the largest tram operator in the country.

Tramway heyday

Over the next fifteen years, an integrated tram system developed. Agreements between the different operators allowed trams to travel on other lines and ‘through’ tickets were introduced.

Tracks were laid over Westminster Bridge in 1906, and the opening of the Kingsway Subway in 1908 connected services north and south of the river. In 1913, London’s three private tram systems were taken over by the Underground Group.

Trams could carry twice as many people as motor buses, and in greater comfort. They were cheap to run, so fares were low, and they were quick and frequent. Despite competition from the first motor buses, the number of passengers using trams grew. The LCC was committed to a policy of low fares to encourage people to use trams and other tram operators were forced to follow suit. At their peak, over 3,000 trams carried a billion passengers a year over 366 miles of track.

After the First World War, the tram began to lose its dominance as the motor bus competed for passengers. In 1923, buses carried more passengers than the trams for the first time, and most of London’s tramways were running at a loss.

By the late 1920s, the new buses offered higher standards of comfort. The pre-war trams were spartan and in need of modernisation. Many tram operators were soon converting routes to buses or trolleybuses.

The tram operators hoped to lure passengers back onto trams with a policy of cheap fares and new cars. In 1926, the LCC began to refurbish its fleet of E/1 type trams with upholstered seats and a new red and cream livery. The private companies developed new prototype luxury trams and, in 1931, the ‘Feltham’ tram went into service. The LCC followed with a new tram type in 1932 and modernised the Kingsway Subway to take double-decker trams. However, this was too little, too late.

Decline and fall

In 1933, a unified London Transport (LT) incorporated all of London’s Underground, bus and tram networks. LT took over 2,600 trams and 327 miles of track. The system was in poor condition and in need of repair and investment.

Increasingly, trams were seen as noisy and dangerous to road users, and costly to taxpayers. In 1931, a Royal Commission had recommended replacing trams with trolleybuses. LT adopted this policy, and the conversion programme began in 1935. By 1940, half of London’s trams had been scrapped. Those surviving were restricted mostly to south of the river.

Ironically, the Second World War, which was to cause so much damage to London’s transport, brought a temporary reprieve for the tram, as necessary repairs and maintenance were done to keep the system running.

In 1946, LT announced that there would be no more tram to trolleybus conversions, and trams were to be replaced by diesel buses. This was done in stages between 1950 and 1952. The last tram left Woolwich for New Cross on 5 July 1952, amidst scenes of great excitement and sadness. Many trams were scrapped, whilst the Feltham trams were sold to the Leeds Corporation, continuing in service until 1959.

Trolleybuses

Trolleybuses, like trams, are powered by electricity taken from overhead wires, but run on pneumatic tyres.

The first rail-less electric trolley vehicle was demonstrated in London in 1909, and two years later the first trolleybus services were started in Leeds and Bradford. London’s first trolleybus service was started by LUT in 1931, replacing trams between Twickenham and Teddington. LT’s tram-to-trolleybus conversion programme began in 1935.

The trolleybus was the obvious replacement for London’s trams, being cheap to run and more manoeuvrable. Existing equipment could be easily converted at half the cost of modernising the tram system. The trolleybuses were popular. They were fast, clean and quiet, and gradually wooed passengers away from trams. At the peak of its service in 1952, following the demise of the tram, London’s trolleybus fleet was the largest in the world, with 1,811 vehicles on 254 miles of route.

The age of the trolleybus was short-lived. In 1954, LT decided to replace them with motor buses, including the new Routemaster. New diesel buses could use cheap fuel, readily available at the time. By contrast, the cost of maintaining and renewing electric overhead wires was high. New routes were needed to serve the growing suburban areas, and buses were not hindered by fixed overhead equipment.

The replacement programme began in 1959, and London’s last trolleybus ran on 9 May 1962, from Wimbledon to Fulwell. After more than sixty years, electric street transport in London was at an end.

Trams in the twenty-first century

The primarily financial decision to end tram and trolleybus services in London was made at a time when the full impact of fossil fuels on the environment was not fully appreciated. In recent decades, electric power has been seen as an increasing necessity.

In May 2000, the Croydon Tramlink system brought trams back to the capital’s streets, running between Wimbledon, Beckenham Junction, Elmers End and New Addington. While this is only a small corner of the Transport for London (TfL) network today, it is part of a much wider effort to change the way London’s public transport network is powered.

You can read more about the major historic transitions in London’s public transport vehicles here: Steam to green: London’s public transport and the environment