Steam to green: London’s public transport and the environment

Introduction

London’s public transport has long been concerned with moving large numbers of people across the city cheaply and efficiently. Sometimes this has gone hand-in-hand with modes of transport that have had a relatively low impact on the environment. On other occasions, economic considerations have outweighed any other. Decisions in the past were also made without the weight of research that we have today on the harmful impact of fossil fuels.

The history of London’s transport system is also one of innovation. The technology available at the time often dictated what was possible, though London’s transport needs often accelerated developments.

Here we look at some of the big transitions in London’s public transport over the last 200 years and their environmental impact.

Underground: steam to electric

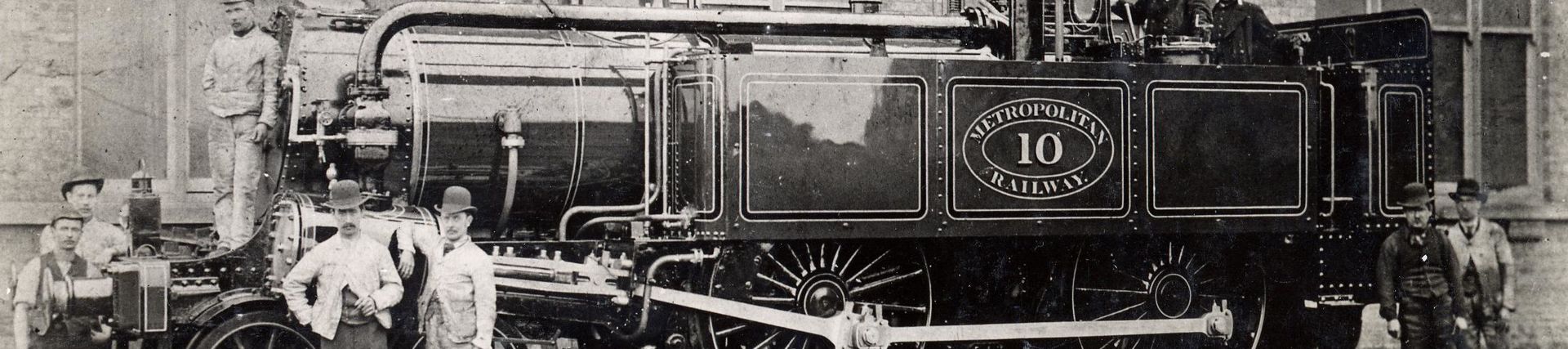

When the Metropolitan Railway between Baker Street and Farringdon Street opened in 1863, it was the world’s first underground railway. At the time the only feasible way for this to be powered was using steam engines, with electric trains not yet invented.

John Fowler, the Metropolitan Railway’s chief engineer, unsuccessfully attempted to develop a steam engine that produced less smoke, steam and fumes. His resulting engine was nicknamed ‘Fowler’s Ghost’, as Fowler was reluctant to discuss his failed experiment.

Ultimately the Metropolitan used steam engines designated ‘A’ class and manufactured by Beyer, Peacock & Company of Manchester between 1864 and 1869. These engines were fitted with condensers to reduce steam in the tunnels. A pipe on each side of the boiler fed exhaust steam from the cylinders into large tanks, where it was condensed into water. While this dealt with the steam, it did not eliminate the smoke. This meant the atmosphere on the early Underground was noxious and unpleasant. The wider expansion of the system, especially deeper underground, was not sustainable without an alternative form of power.

Fortunately, an alternative transformed the Underground. In 1890, the City & South London Railway (C&SLR) opened between Stockwell in south London and King William Street in the City. This was the world’s first electric deep level underground railway. It was made possible by several major innovations: the ability to dig tunnels deep underground using a protective shield; the ability to move passengers deeper underground with hydraulic lifts; and the ability to power the trains with electric traction.

The C&SLR was originally intended to use cable haulage powered by steam engines. During construction it became clear that electric traction could be used instead. The railway used small electric locomotives designed by Edward Hopkinson and built by Mather & Platt of Manchester. They were so experimental that they had never been tested in the railway’s narrow tunnels and often touched the walls on sharp bends. They also struggled to pull heavy loads due to their relative lack of power.

Even so, these electric locomotives were revolutionary and transformational, paving the way for the Underground to expand deeper and further, and also pointing the way for metro systems across the world. While the electricity that powered them came from fossil fuel-fired power stations, this still represented a relatively green form of mass transport compared to the steam engines that came before.

On the surface: the end of horse power

Throughout the nineteenth century, London’s roads were dominated by horse-drawn vehicles. From 1829, horse-drawn carts and private cabs were joined by the first conventional bus services. Buses quickly evolved into double-deck vehicles with rear staircases.

From 1870, buses were joined by horse-drawn trams that ran on rails in the roads, making them easier to pull. This meant they could carry more people and so offer cheaper fares, making them the first genuinely affordable means of public transport for working-class Londoners. Trams were not allowed in central London, but rapidly expanded along most of the city’s inner suburban main roads.

While all this horse-drawn transport was relatively green, it did have an environmental impact. In late Victorian London, public transport required 50,000 horses, who ate 250,000 acres of foodstuff a year and deposited 1,000 tonnes of manure on the streets every day.

In the 1880s London tramway companies began to try out alternatives to horse power. The first cable tramway in Europe was opened at Highgate Hill in 1884. There were also experiments with battery and steam-powered trams. The London County Council (LCC) took over many of the horse tram routes in the 1890s, progressively electrifying them. By 1910 the LCC had 120 miles of electric tram routes.

Simultaneously, buses were also undergoing a revolution. Experimentation with sources of power led to battery-electric buses as early as 1906. But it was the development of the internal combustion engine that became dominant. In London buses, this really took hold with the B type, the first mass-produced motorbus in the world when it was introduced in 1908. Between then and the First World War in 1914, the London General Omnibus Company – London’s biggest operator at the time – replaced all its horse buses and other types of early motorbus with B types.

The B type was powered by a 30-horsepower petrol engine. Its new dominance of London’s streets coincided with the rise of motoring generally, and a subsequent increase of fuel emissions through the twentieth century.

On the surface: the end of trams and trolleybuses

From the 1870s to the 1950s, trams were a common sight on London’s streets. By the early twentieth century, an extensive network was powered by electricity through overhead cables or a conduit underneath. While most of this electricity came via fossil fuel-fired power stations, they were a largely environmentally friendly mode of transport with large capacity, which hugely reduced the vast resources that using horse power relied upon. The downside was that they were fairly expensive to maintain.

In the 1930s, trams were joined by trolleybuses. These unusual vehicles were also powered by overhead electrical cables but ran on tyres and so had the advantage of being able to pull up to the kerbside, increasing safety and convenience. From 1933, when a unified London Transport was created, the city’s public transport featured an integrated system of buses, trams, trolleybuses and Underground trains, with all except buses powered by electricity.

However, the Second World War and its aftermath created highly challenging economic circumstances. In a period of shortages, the cost of repairing and maintaining the bomb-damaged electrical network necessary for trams and trolleybuses was weighed against the price of a new standardised and efficient bus fleet. London Transport developed the Routemaster in 1954, a bus that was cheap to run and easy to maintain, specifically designed to have interchangeable parts.

The roll out of the diesel-powered Routemaster, alongside the existing large fleet of RT type buses, led to the end of the tram and trolleybus network in London, the last trolleybus service ending in 1962. While this meant the removal of overhead electrical cabling and rails from London’s streets, it also resulted in a more polluting fleet of vehicles.

If LT had possessed the weight of research on emissions we have now in the 1950s, perhaps a different decision would have been made. Though it is important to remember that LT was also competing with the rise in private car ownership – a fleet of economical buses was greener than thousands upon thousands of cars. Today, other than in a small part of south London in the Croydon area, trams no longer run on London’s streets.

A greener future

Since its creation in 2000, Transport for London (TfL) has increasingly looked to greener methods of public transport. With the harmful effects of emissions on Londoners and the wider global climate now more understood, the balance of decision-making has shifted. It is now often not what the cheapest and most practical method is, but what is the greenest.

One of the most obvious areas of change in recent years is in buses. In 2016, the world’s first electric double decker bus was unveiled by TfL. By 2021, TfL had an electric bus fleet of 500 buses and also unveiled the first hydrogen double decker bus in England. By 2030, TfL aims to make all London buses zero emission and, as of 2021, there are 3,500 zero emission capable licenced black taxis in operation.

All passenger rail services operated by TfL are electrically powered. TfL has the target of achieving a zero-carbon railway by 2030, as part of the Mayor of London’s environment strategy. TfL is one of the largest consumers of electricity in the UK, using the equivalent electricity of 437,000 homes, representing 12% of London’s homes. Currently this comes from the National Grid, but TfL plans to source renewable electricity.

There have been numerous other areas of development in the TfL era. This has included the Congestion Charge introduced in 2003 to discourage the use of polluting private vehicles in central London, with the introduction of an extended Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) in 2021. Cycling has been heavily promoted through the Cycle Hire scheme and the creation of more Cycle Superhighways. TfL has also promoted walking through initiatives like Legible London, whose wayfinding signs help and encourage pedestrians to navigate the city on foot.

Public transport clearly continues to have a vital function in getting Londoners from place to place, and increasingly seeks environmentally friendly ways of doing so.