A brief history of the Thames Tunnel and the East London line

There is something of Trigger’s broom (or the Ship of Theseus if you’re feeling classical) about the old East London line. Running from Shoreditch to New Cross and New Cross Gate, it made its debut on the Tube map in 1914 as an independent railway.

Between 1934 and 1969, it was shown in the same burgundy colour as part of the Metropolitan line. From November 1969 to 1989, it regained a separate identity as the East London Section of the Metropolitan, turning orange on the map a year later. Canada Water station was added in 1999, only for it to be closed in 2007 to reopen once again as part of the London Overground as it continues to exist. No wonder it had a bit of an identity crisis at the time.

But the adaptability of this little section of London’s rail network between Wapping and Rotherhithe predates even its role as part of the London Underground. The section of underground railway between Wapping and New Cross has been open for public traffic since 7 December 1869, but the tunnel’s existence goes back decades earlier.

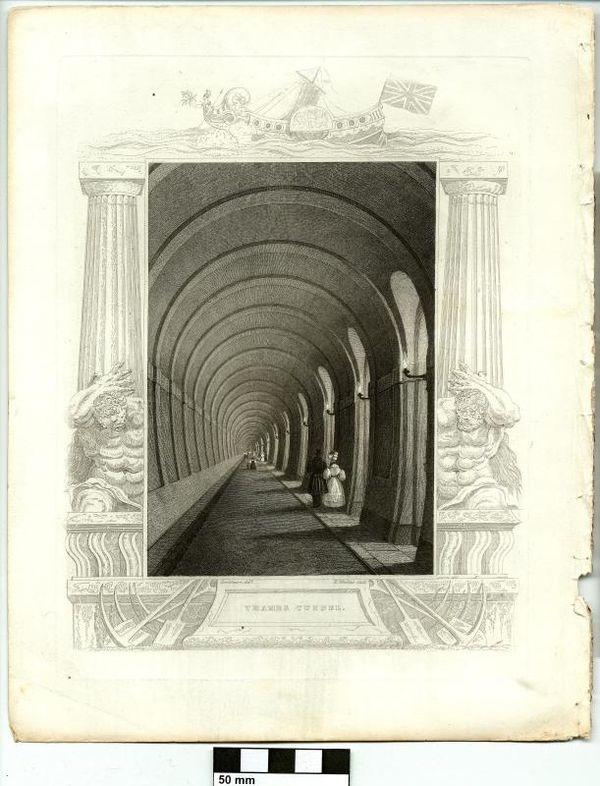

In 1825, French engineer Marc Brunel started work on the Thames Tunnel, the very first underwater tunnel anywhere in the world. Beset by financial difficulties, frequent flooding and several deaths, the project wasn’t completed until 1843. However, it opened not as a thoroughfare for goods as it had been intended but as a pedestrian walkway.

The Thames Tunnel was immensely popular as a tourist attraction when it first opened on 25 March 1843 with one million visitors in its first ten weeks.

Later, the tunnel fell out of favour with the public and became a far less desirous location, earning itself the nickname, the Hades Hotel. The tunnel was sold to the East London Railway in 1865 for £200,000 and was formally handed over on 25 September.

Today, trains continue to go through the railway tunnel several times an hour, making it difficult to see the original tunnel, but the Brunel Museum tells the story of the creation of the Thames Tunnel, on the site of the Engine House and the original tunnel shaft sunk into the ground. The team at Brunel Museum look forward to welcoming you back.