Charles Tyson Yerkes: the unscrupulous American businessman who transformed the Tube

Introduction

A flamboyant financier, Charles Tyson Yerkes played a major role in the electrification and expansion of London’s Underground network, forming the Bakerloo, Piccadilly, and Northern Tubes, nicknamed the ‘Yerkes Tubes’.

Yerkes used shrewd and sometimes shady tactics that proved necessary to realise a modern Tube network for the twentieth century. He founded the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) in 1902, which brought together several modes of transport under one umbrella, ultimately moving towards a unified and cooperative transport system.

Earnest beginnings to profit-making ventures

Yerkes was born on 25 June 1837 to a Quaker family in Philadelphia. Initially, he started his career in an unpaid role as a clerk for a grain commission broker. At the age of 21, he independently set out to pursue what would become a turbulent career dealing bonds in the stock exchange. With growing financial success, he opened his own banking house in Philadelphia, specialising in the sale of government, state and city bonds.

However, disaster loomed. In 1871, the “Great” Chicago fire destroyed the commercial district. A nationwide crisis of confidence ensued and interest in the purchase of bonds collapsed. Yerkes fell out of favour, making enemies. For a period, he was imprisoned for embezzlement. Evidently, this did not faze him. A newspaper report quotes him saying ‘I have made up my mind to keep my mental strength unimpaired and think my chances for… regaining my former position, financially, are as good as they ever were’.

In his search for profit-making ventures, Yerkes became attracted to the rich and expanding city of Chicago. His interest peaked when he became involved in the development of the tramway and suburban railways systems. Through astute and convoluted business dealings, Yerkes carried out the electrification of North Chicago City Railway and North Chicago Street Railway. His solution to the lack of a terminal in the city centre, the ‘Loop’ as it is referred to, is one of Chicago’s most renowned structures to this day.

However, his ruthless business methods became increasingly disreputable and he was forced to leave Chicago. Without having spent or risked his own money, he made for New York with a fortune of $15 million – in cash!

Moneytrain

The world’s first underground electric railway, the City & South London Railway, opened in 1890. It had seen great popularity but had been a commercial disappointment. Consequently, this made it impossible to raise the necessary capital in Britain for further projects.

The District Railway was just one project left unfunded and in urgent need of renewal. Former solicitor to the Metropolitan Railway, Robert W Perks, had the foresight to look to America for financial investment and specifically to Yerkes. Together, they believed that moving from steam to an electrified system would substantially improve the District’s performance.

Electrifying the District line

Yerkes’ first investment took place in 1898 and by March 1901 Yerkes had control of the District line. Forming the Metropolitan District Electric Traction Company (MDET) in July of that year, Yerkes raised £1 million to invest in the company – 95% of which came from American shareholders.

After a lengthy, controversial and public dispute with the Metropolitan Board, Yerkes won his battle to electrify the District using a high voltage alternating current. On 28 March 1905 the first successful trial run of an electric train took place from Mill Hill Park (Acton Town) along the southern section of the Inner Circle. The electrification of the line was completed on 1 July 1905.

Lots Road

With no electrical supply industry at the time, it was decided that one vast power station would be built as a pioneering solution to supply the District.

Between 1902 and 1905, Lots Road in Chelsea was constructed and was for a short time the largest power station in Europe. It later took over supplies for the rest of the Tube system.

Despite proposals from Yerkes for inclusion, the Metropolitan chose to remain independent and built its own power station in Neasden and continued to use steam on its extension line – electrification was not completed until 1961.

Underground Electric Railways Company of London – expanding the network

During the proceedings to electrify the District, Yerkes founded the Underground Electric Railways Company of London (UERL) in 1902, which later became the Underground Group. At the time, he had already begun the process of taking over struggling new Tube projects and taken extreme measures to outmanoeuvre competitors and monopolise business deals. One rival syndicate referred to dealings with Yerkes at this time as ‘the greatest rascality and conspiracy I ever heard of’. The UERL swiftly took control of three new lines.

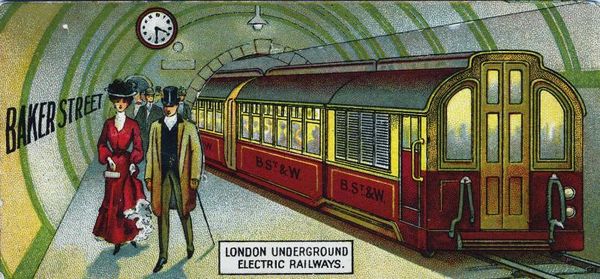

The first was the Baker Street & Waterloo Railway, which opened for business in March 1906 and later became the Bakerloo line.

The second combined two projects to create the Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway. It opened in 1906 and ran from Finsbury Park to Hammersmith with a short branch from Holborn to Aldwych.

Thirdly, there was the deep-level Charing Cross, Euston & Hampstead Railway, which Yerkes obtained parliamentary authorisation to build and in 1900 paid £100,000 to acquire control of the company.

He became its Chairman and Perks a director and the line opened in June 1907. This was to run from Charing Cross to Camden, but Yerkes saw the potential for suburban development extending to Golders Green, which was in open country. Originally known as the Hampstead Tube, it eventually became the Northern line.

Yerkes employed architect Leslie Green to decorate the lines, commonly referred to as the ‘Yerkes Tubes’, in his distinctive Arts and Crafts influenced style to keep a unified appearance.

Integrated London-wide transport system

In spite of Yerkes’ sometimes exploitative schemes and suspicious transactions, he was extremely forward thinking. As well as bringing the new Tube lines together under the UERL, Yerkes saw the benefit of a more integrated London-wide transport system that would eventually also include buses and trams. Ahead of his time, he also wanted to introduce fare zones. He is recorded as stating that the pinnacle of transport in London:

…would be that a person could travel from any one point to any other point, making connections from one line to another, all for a single fare. That would be perfection of travel, and it will never come about unless there is an amalgamation of the railways.

Unfortunately, despite his instruction, the idea was dropped and instead return fares to the City were reduced, as a result of which traffic grew.

‘One of our Conquerors’

Charles Tyson Yerkes was the driving force in the revolution in London’s railway transport in the first decade of the 20th century. His unorthodox methods were regarded with distaste in London business and financial circles and many were astonished by his formation of the UERL. He brought with him a reputation of deception.

However, by 1913, the Underground Group controlled most of London’s tube network, as well as London’s largest bus company and three tramways. It later took over the Central London and the City & South London, creating the pre-1914 Traffic Combine, which paved the way for the final amalgamation of London Transport in 1933.

Yerkes did not live to see the completion of the Yerkes Tubes. He passed away on 29 December 1905. Having performed what some described as ‘financial wizardry’ to carry out his achievements, his London venture had ultimately not added to his fortune, pushing his personal finances into confusion and debt. He left his shareholders indignant and impoverished.

Most, if not all, of his estate that he had bequeathed to the City of New York had to be sold at auction to cover his outstanding debts.