James Greathead and tunnels under London

Tunnelling

Tunnelling developed from mining. In the nineteenth century it was costly, unpredictable and very dangerous. Even so, when the French engineer Marc Brunel began work on the first tunnel under the River Thames in 1825, he was confident that his new ‘shield’ invention would protect workers as they dug. He underestimated the practical and financial difficulties ahead, and the project took nearly twenty years to complete. But when the Thames Tunnel opened it was hailed as an engineering marvel.

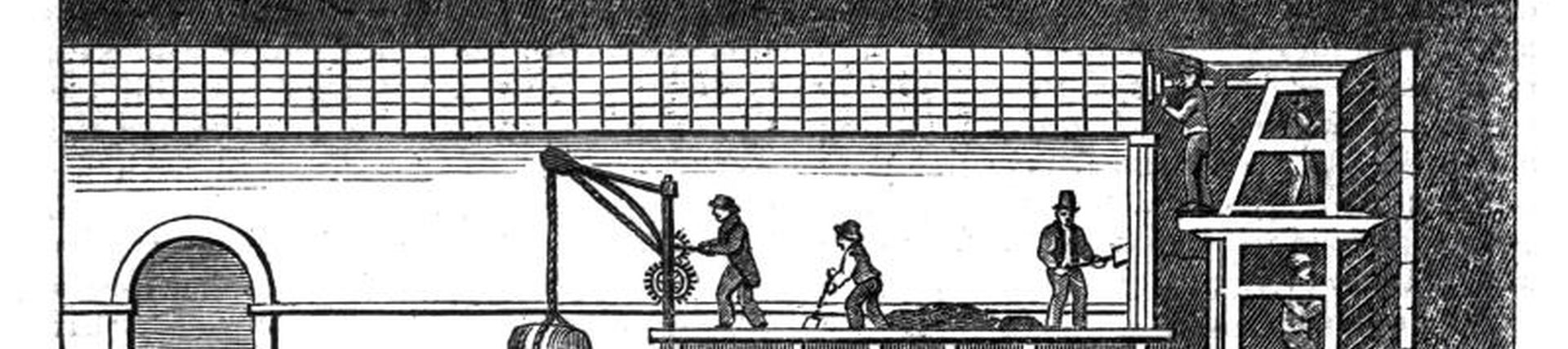

Using Brunel’s shield, workers dug from within a protective wooden structure, with the tunnel walls being built up behind. However, the tunnels were prone to leaks from the riverbed, not far above. In the worst flood in 1828, six men drowned. The work was stalled for eight years.

In 1862 the engineer William Barlow watched as tubular girders were pushed into the soft bed of the Thames for the foundations of Lambeth Bridge. They gave him the idea for a circular shield, pushing through the layer of clay under the river like an apple corer. It was Barlow’s concept, but it took the work of his former apprentice, James Greathead, to develop a practical tool to do the job. The world’s first tube tunnel, cut with Greathead’s shield, was the Tower Subway that opened in 1870. Just seven feet (2.13 metres) wide, it was dug under the Thames from the Tower of London.

In 1886 Greathead was appointed as engineer to a new project, the City & South London Railway, which became the first electric tube railway in the world four years later. He enlarged and improved the shield and equipped it with hydraulic power and compressed air. Greathead died in 1896, but the tunnelling machines that took his name spread the tube railway network right across London in the next ten years. Greathead shields were still in use in the 1940s, with only minor changes.

In the 1960s work began on the Victoria line, the first brand new line for over half a century. The new ‘rotary excavator’ shields used to cut the new tunnels accommodated automated conveyors to dispose of spoil efficiently. Shields based on Greathead’s design incorporating rotary cutters were used in London as early as 1897. They suffered from problems for many years but were perfected by the 1960s. Pre-cast concrete segments replaced the traditional cast iron rings on much of the line.

Today in tunnelling projects, machines are more in evidence than man, but they still rely on the shield principle Greathead established in 1870. The UK’s first fully automated Tunnel Boring Machines (TBMs) cut the Jubilee line extension to Stratford in the 1990s. These huge machines incorporate an integrated system of digging, tunnel-building and waste removal, guided by computers. Eight TBMs, costing £10 million each, dug 42 kilometres of new tunnels for the Elizabeth line between 2012 and 2015. Most recently TBMs have been used on 6.4km of new tunnels on the Northern line extension from Kennington to Battersea Power Station.